1815-1893

to

Helen Davidson

Garrett Farrell

I

Sarah Glenmire Farrell

I

James Henry Davidson

I

Helen Davidson

Birth/baptism:

Father:

Mother:

Marriage:

Death:

Children:

1815, Cork, Ireland

Garrett Farrell

M. Anne Cotter

Jane Clark, 9 June, 1850, Newstead station, nr Inverell NSW

3 March, 1893, Booralong, NSW

Margaret (1852-1868)

John (1853-1946)

William (1856-1908)

Mary (1858 -1944)

James (1860-1865)

Andrew (1862-1948)

Emily (1864-1897)

Sarah (1868-1901) m. David Johnstone Davidson, in Armidale, NSW 1891,

Garrett Farrell was both a reliable hard worker (according to his employer) and a trouble-making rabble rousing traitor (according to a police prosecutor) – and both these aspects of his character were on show in a court case in Grafton in the 1860s. Fortunately for Garrett, the judge and jury didn't agree with the police.

And how did he get to that predicament in the first place? In common with many young Irishmen of the time, he was both keen to escape the poverty of his native land, and felt no particular loyalty to the English Crown. And although the Crown was the nominal ruler of the relatively new state of New South Wales, Garrett did not let that authority stand in the way of going to make a better life for himself in the southern lands.

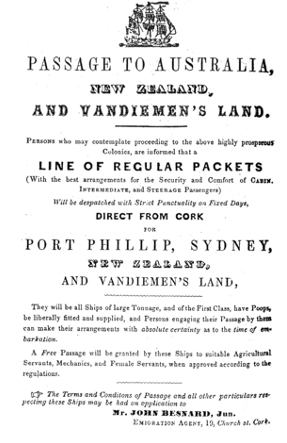

In the 1830s and into the 1840s, these advertisements (at left) were common in the British Isles, seeking to attract young immigrants for labour-starved agricultural properties in New South Wales - and 24 year old Garrett, was one who responded. The attraction, of course, was the free passage it offered to approved "agricultural servants, mechanics. and female servants". So Garrett signed up for a voyage to Sydney on the Navarino, in 1839.On his arrival papers, Garrett was simply described as a "labourer". His new employer HC Sempill had just started Belltrees a property in the Hunter Valley near Scone, and while Sempill had other properties on the New England tablelands, Garrett was first destined for his Hunter Valley run.

We have no reports of his time at Belltrees, but in the early 1840s, he probably was sent north to Newstead, one of the Sempill runs in the New England. (By the mid 1840s, Sempill had run into financial difficulties along with many other pastoralists in the colony, and had sold up to return to England. Belltrees' new owners were the White family which included Nobel-prizewinning novelist, Patrick White. The Whites have owned Belltrees for more than 170years).

Newstead also has a claim to fame outside agricultural circles - its woolshed was painted by Tom Roberts in the 1890s, in a work entitled The Golden Fleece. According to the Art Gallery of New South Wales,

(Originally called 'Shearing at Newstead'), the painting was renamed to reference the Greek myth in which the Argonauts voyage to the end of the world in search of the Golden Fleece. The title reflects Roberts' creation of the rural worker as 'hero', and his evocation of Australia as an Arcadian land of pastoral plenty.

An Irish family, that of John and Sarah Clark, had arrived at neighbouring Ollera station probably in 1850 coming from another neighbouring station, Moredun, after landing in Sydney in 1845. That family included young Jane, who was barely 16 years old when she and Garrett married, at Newstead in 1850. By the early 1850s, Garrett had left Newstead and was living and working as a shepherd on Ollera station, a connection which was to last for the rest of his life.

At Ollera, Garrett had found his lifetime home. From labouring and working as a shepherd on the station, he grew to become the property's most trusted teamster, responsible for many long distance overland trips from the highlands to deliver wool to Grafton and Morpeth (both coastal river ports - Grafton on the Clarence R, and Morpeth on the Hunter R.). His work was documented in the Ollera registers where he was described as the "station's valued long-distance bullock driver"

Garrett's work schedule was demanding. In one year, the records show he completed two bullock-team trips of approximately 250 mountainous kilometres each way from Ollera to Grafton, carrying nearly two tons of wool each time, within a space of two weeks, before backing up to do a similar expedition to Morpeth. The station owners were the Everett brothers, who evidently had a paternalistic attitude to their workers, often rewarding them for good work with significant bonuses. One such occasion came in the 1850s, when Garrett received what is said to have been an "especially generous" present of £10 after an unusually long and difficult trip 'down country'.

It was on one of his droving trips to Grafton that Garrett ran into strife with the law. Like many Irishmen, then and later, he had little time for the English Crown, and according to testimony given to a jury, when under the influence of alcohol, he used extremely derogatory terms to describe Queen Victoria.

The incident was first reported in The Clarence and Richmond Examiner of 16 June, 1868:

Garrett Farrell, an Irishman, was brought before tho Court, In the custody of constable Tierney, having been given in charge by Mr. Alderman C. Avery, at South Grafton, on a charge of making use of disrespectful language towards her Majesty the Queen, contrary to the provisions of the Treason Felony Act. Patrick Tierney deposed: he was a constable in the Grafton Police force, stationed at South Grafton ; the prisoner was given into his charge by Mr. Charles Avery, about seven o'clock on Tuesday evening last, on a charge of using disrespectful language towards her Majesty ;

He told the prisoner the charge; he made no reply; he brought him to the lock-up, and whilst on his way thither, the prisoner remarked to another man, who he met at the Ferry Wharf, ''They could not hang him". The prisoner had been drinking, but knew what he was doing.

Charles Avery deposed: he was a contractor, residing at South Grafton; he gave the prisoner in charge on Tuesday evening; the prisoner had been drinking a little at Mr. Cowan's public-house, South Grafton, after which he commenced abusing the Queen and England. He remonstrated with the prisoner and told him he ought to be ashamed of himself to use such language towards the Queen of England, and cautioned the prisoner that if he did not desist he would give him in charge of the first constable he could find; prisoner then made use of further disrespectful language towards her Majesty.

The witness then went to look for a constable and gave the prisoner in charge.

Thomas Wray stated that he was present, and heard the prisoner making use of disrespectful language towards her Majesty the Queen several times.

The prisoner when asked if he wished to make any statement, said he had been drinking, and could not recollect anything that he stated at the time, was then committed to take his trial at the next Court of Quarter Sessions [..] at Grafton, on Monday, the 3rd of August next, on a charge of making us of disrespectful language towards her Majesty the Queen, contrary to the provisions of the Treason's Felony Act.

The prisoner was then removed in custody, but on Friday was released on bail, prisoner in £100, and two sureties of £50 each.

At

his next appearance on the charge, the Judge said he was pleased

with the continuing bail Garrett was being afforded, and said he did

not think there was such a thing as Fenianism

in the country, and told him that he thought it was very probable he

would not be tried for the offence.

At

his next appearance on the charge, the Judge said he was pleased

with the continuing bail Garrett was being afforded, and said he did

not think there was such a thing as Fenianism

in the country, and told him that he thought it was very probable he

would not be tried for the offence. Nonetheless, Garrett did eventually did go to trial at Grafton courthouse, where the jury was told he had been "winding up a spree" and after "some provocation" had made "use of certain language disrespectful to Her Majesty the Queen". The main prosecution witness (Charles Avery), pleading illness, failed to turn up for the trial. Various identities from the New England area, including his employer, Edwin Everett, and the Ollera station superintendent James Mackenzie, gave Garrett excellent character references.

The jury came down in Garrett's favour, and the judge discharged him from custody, after warning him to be more careful "when taking his cups in future".

By this time,....

The Crown Lands Act of 1861was designed to break up the control of vast sheep and cattle properties by the privileged graziers who paid what was thought a pittance for unfettered access to the runs. The intention of the Act was to allow "selectors" to obtain land via conditional purchases, thus taking control of the land away from the landed gentry. However, many employees of these big runs were thought to have made "dummy" applications for key parcels of land, which were then sold back to their employers. It appears that the Farrell family, both Garrett and two of his sons, John and Andrew, may have cooperated in this manouevre.

After his bullock-driving days were over, Garrett was still maintained on Ollera, as a shepherd and then as a 'pensioner', although its owner, Edwin Everett the youngest of the three Everett brothers, at times appeared to begrudge the payments to him. In 1890, three years before Garrett's death, Edwin waspishly asserted that they were paying Garrett too much, describing him as "old and worn out", and paid too much (£40pa) for "half a flock and fenced nearly all round". Edwin's older brother John, the original settler of the station, had a far more generous view according to the New England historian, Margaret Rodwell (see below):

But leave Ollera he did, if only to travel the 50 kilometres to his daughter's home at Booralong, where his died in 1893 in his seventies. However, his remains did return to the station where he had lived almost all his adult life - Garrett is buried in the historic graveyard near the church of St Bartholomew at Ollera.

*****

Back to Davidson Family Tree