This block will be replaced by LeftMenuGaffey (orByrnes) when the page is served from a server.

- Birth:

- c1770 . Ireland [1], [2]

- Convicted:

- of theft from a warehouse, Apr 1798 in Dublin [3], [4]

- Sentenced to:

- 7 years (Apr 1798) [5]

- Transported:

- 1799/1800 in NSW[6],[7]

- Occupation:

- Farmer (bet 1800 and 1833)[8],[9],[10]

- Death:

- Jan 27 1833 in Cornwallis, near Windsor[11]

- Burial:

- 1833 in Windsor R/C[12]

- Probate:

- Mar 1833 in Sydney[13]

- Spouse (1):

- Catherine ?????

- Children:

- John PENDERGAST (1800-1867)

- Spouse (2):

- Jane

WILLIAMS

(1802/3 in Parramatta, NSW (presumed de facto)

- Children:

- James PENDERGAST (1803 – 1865), married Sophia Hancy, 1828, Parramatta

- Thomas PENDERGAST (1805-1862)

- Sarah PENDERGAST (1806-1873)

- William PENDERGAST (1808-1850)

- Bridget PENDERGAST (1810-1885)

Actual birth or baptism details for John have so far not been found, but some biographers have recorded that he was born in Dublin, Ireland in 1769, and according to his wife Jane Williams' biographer Veronica C E O'Brien Sitton[15], he came from one of the "distinguished Norman-Irish families of Ireland".This last claim might be a bit of a stretch, since on the convict records John was a labourer, and other later evidence indicates he was illiterate.

The Australian Biographical and Genealogical Record, Series 1, 1788-1841 says : "Available evidence indicates that John Pendergast “was transported for participating in the 1798 Irish Rebellion". However, the revolt was launched -and suppressed - in May, 1798, and the date of John's conviction was recorded as being a month earlier, in April 1798. Dublin's Freeman's Journal of April 28, 1798 in fact tells the story of John's crime, that he, along with four others, raided a warehouse and stole "two hogsheads of tobacco, a quantity of bark (?), sugar, and a box of Godbold's Vegetable Balsam". The prisoners were found guilty of the theft to the amount of 4 shillings and 9 pence each, and all five were sentenced to be transported for seven years.

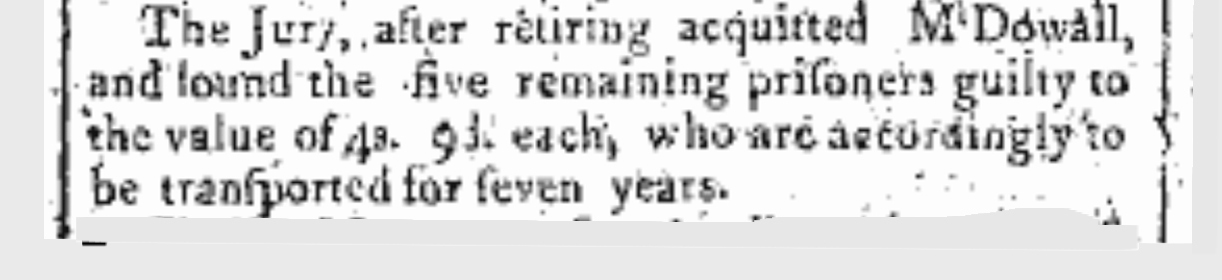

The following is an extract from the Freeman's Journal with the account of the court case and a transcription (note in the 18th and 19th centuries it was common to use what looked like an"f" in some instances as an "s"):

QUARTER SESSIONS.

TUESDAY APRIL 24

(...)

John

Harrington, Francis McDowall, Edward Dunn, John Prendergast,

Con Molony, and James Kelly, were next to the bar. On a charge

laid capitally, for having on the 15th inst. stolen out

of the ware-house of Henry Warren White, two hogsheads of tobacco,

a quantity of bark, sugar, etc with a box of Godbold’s Vegetable

Balsam, value 20(?)

Robert Tecling(?)

deposed that he knew of the felony having been committed,

but could not charge the prisoners with it. Ryder, a constable of

the Watch in St Mary’s parish identified the prisoners whom he

took in consequence of having received information the stolen

goods were lodged in the stables of Alderman Lynam at the Lo…. He

went thither, accompanied by a few watchmen, and on using threats

to the prisoner Harrington, who replied to him from within the

stable, the door was at length opened.

On interrogating him as to the stolen goods, he

acknowledged to the witness to have smuggled tobacco in his care,

and told him that the persons who lodged it were there on the

premises, on which the witness has been apprehended.

The prisoner Dunn acknowledged that the tobacco was had

at the opposite stores – a box of Godbold’s Vegetable Balsam, and

an handkerchief containing seven pounds of sugar were found with

the prisoner Harrington. Mr White proved his property in the

quantity of tobacco found, principally from the report of the

Inspector of Tobacco who told him it exactly agreed in weight with

the quantity missing to a pound. The Inspector of Tobacco who

happened to be foreman of the Jury, corroborated that part of Mr

White’s testimony, which referred to him.

Mr Green, as Counsel for Harrington and Kelly, two servants belong to Alderman Lynam, made a very ingenious defence, on the ground of a practice, though, he said, extremely culpable, yet did not by any construction of law amount to a felony, that of harbouring smuggled goods. The story which Harrington told the Constable of the Watch carried a conviction of its truth on the face of it by his promptness in mentioning the names of the men who left the tobacco in his charge which he would not do with much struggle and hesitation had they been his confederates in a capital felony. The box of Balsam and the sugar Harrington acknowledged to have received from them as part of a gratuity for his care. The prisoner Kelly he looked upon to have been deluded on the same principle and if any regard could be had to character to elucidate a fact of this nature, wrapped up in mystery and doubt, his clients were singularly happy in that point.

Alderman Lynam and another gentleman deposed in very strong terms the uncommon fidelity of Harrington and Kelly. The Recorder, in his charge told the Jury, that under very strong circumstances of guilt in the prisoners, particularly three of them – against McDowall no evidence appeared, having been apprehended elsewhere barely on suspicion; still if they entertained a doubt, they might by the verdict render the punishment transportation, but stating the value of the article stolen at 4s 9d. each.

So, John sailed on Minerva, a vessel noted as carrying Irish

rebels, which after leaving Cork in August 1799, arrived in Sydney on

January 11, 1800. To add to the uncertainty, the convict indent

for the Minerva lists John as an Irish Rebel....

Where John married his his first wife Catherine isn't known. However, their one son John, was born in the colony c1800, possibly soon after the arrival of the Minerva. There has been speculation that John and Catherine had earlier married in Dublin, and that Catherine was one of the four unnamed passengers on the Minerva (in addition to the soldiers and convicts on board). However, these passengers are not named in official records.

As a convict, John was not able to own land, but in 1800-1802, Catherine (as Mrs Pendergast) is recorded as being the purchaser of three land parcels at Mulgrave Place (soon to be renamed Pitt Town Bottoms). Catherine must have been a woman of some means, to be able to buy these parcels of land from the original grantees. She also gained the services of an English girl, Jane Williams, a convict who was transported in December 1801, on the Nile. Catherine then disappeared from the record books. No burial in her name has been recorded. It's also considered possible she returned to Ireland - but again, no records have survived.

After Catherine disappeared from the scene, Jane Williams, the convict who had been assigned to Catherine, began to live with John as man and wife at Windsor. No official records of a Pendergast -Williams marriage have been found, but as noted by her biographer, John was a Catholic, and no Catholic priests were allowed to operate as priests in the Colony at that time - at least not officially. At one stage, official records show that John lived in a state of concubinage[16] He was given a conditional pardon, even though his sentence was for only seven years,. The effect of a conditional pardon was to block him from ever going home to Ireland - a very severe restriction.

The Muster of 1802 shows that John's farm of 30 acres, growing wheat

and maize, was held in partnership with James Clark; by 1806, he had

115 acres to his name. Establishing himself in the Hawkesbury district

would not have been easy- severe floods had devastated the area, and

John was struggling to pay his debts.

In 1808 the Provost Marshall had put some of his property up for sale:

“Two farms situated contiguous to Cornwallis known by the name of Pender’s farm and containing 60 acres more or less…with 40 acres under wheat.. Likewise a farm situate down the Hawkesbury River formerly Adlam’s Farm – the whole the property of John Pender” (Sydney Gazette, 23 October 1808).

However, the sales did not proceed - we can only assume John came good with whatever money was needed at that time, but again, he faced further action in the Court of Civil Jurisdiction between 1810-1814 for other business problems[17].

Eventually, however, John became an astute businessman, acquiring

more land, both by grant and purchase, at Cornwallis, Lower Portland, Kurrajong, Windsor and Wollombi.

Cornwallis, Lower Portland, Kurrajong, Windsor and Wollombi.

The Wollombi connection is interesting. John's son Thomas also had property there (as well as the Monaro district) and went on to become the second licensee of the Rising Sun Inn, at Millfield (right). Thomas has been described as a "colourful character". In 1840, the inn was held up by a notorious bushranger gang, that of Edward ("Jew Boy") Davis. Thomas was robbed of £13, but he was more fortunate than another victim. A visitor to the inn on that night was previous licensee John McDougall, who was whipped by the bushrangers in revenge for his treatment of convicts while he'd been a convict overseer[18].

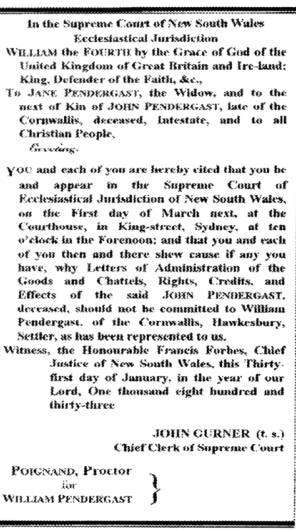

In January, 1833, John Pendergast died at his home at Cornwallis, without leaving a will.

A legal notice (see left) was published in the Sydney Gazette of February 5, 1833, by solicitors representing his son William, calling on his mother and John Pendergast's next of kin, to show cause why the remaining estate should not be handed over to William (Pendergast's fourth son, after John, James, and Thomas). This notice was issued on January 31st, only four days after John Pendergast's death. However, the letters of administration granted by the NSW Supreme Court for the estate suggest that the arrangement was amicable. (At the time of the 1828 census, William was the only one of John's sons still living at his parent's home).

The lack of a will is not as thoughtless as it may seem. Shortly before his death, John transferred several properties to his sons John, James and William, and Thomas's son John. Thomas himself was not a beneficiary, but by that time Thomas had established himself with considerable property of his own, in the Monaro district.[19]

NOTE: For the information on Catherine Pendergast's land purchases, and John Pendergast's conviction in Dublin in 1798, I am indebted to fellow Pendergast researcher Jennifer Wood and her genealogy writings at www.familiesofireland.com.[1] Michelle Nichols. Hawkesbury Pioneer Register. Hawkesbury Family History roup. page 143.

[2] compiled and edited by Dr C J Smee. Pioneer Register 2nd Ed. Vol. 2.

[3] Veronica C E O'Brien Sitton. Jane Williams Pendergast 1775/6-1838 an unpublished monograph submitted for the Australian Biographical and Genealogicial Record (ABGR). Held at the Hawkesbury Public LIbrary. Veronica C E O'Brien Sitton, Oregon U S A 1984. Apprendix III

[4] Freeman's Journal, Dublin, 28 April, 1798; John T Spurway (editor). Australian Biographical & Genealogical Record, Series 1 1788-1841. ABGR in association with the Society of Australian Genealogists.

[5] John T Spurway (editor) As above p331

[6] Michelle Nichols. Hawkesbury Pioneer Register. Hawkesbury Family History Group. page 143.

[7] John T Spurway (editor) op.cit.. p 332.

[8] Census/Muster

[9] Veronica C E O'Brien Sitton. Jane Williams Pendergast 1775/6-1838 Op.cit. Appendix II

[10] Michelle Nichols. Hawkesbury Pioneer Register. Hawkesbury Family History Group

[11] As above page 143

[12] As above

[13] Sydney Gazette. February 5, 1833

[15] Veronica C E O'Brien Sitton. Jane Williams Pendergast 1775/6-1838 Op.cit. Appendix II

[16] Jan Barkley, Michelle Nichols, Hawkesbury 1794-1994: The First 200 Years of the Second Colonisation, Hawkesbury City Council, 1994, Appendix 5, p16

[17] See NSW State Records item: 5:1103.

[18] a pamphlet issued by the Rising Sun Inn c2005 to promote the history of the Inn

[19] Michelle Nichols, A Brief History of the Land at Upper Half Moon Reach, Hawkesbury River, http://www.hawkesbury.net.au/cemetery/half_moon_farm/history.pdf 1995