Alfred Boddy Annie Boddy

![]()

Geoffrey Alfred Boddy

Birth:

1864, Dover UK

Marriage:

Charles Richards, 20 July, 1884, Woolwich, London

Death:

1909, Sydney Hospital, Sydney, NSW

Father:

Mother:

Children:

Herbert Charles RICHARDS (1887-1961)

John Oliver BODDY(1903-1903)

A hint that Annie Boddy's life was not going too smoothly came in her father's will. Although George Boddy made a bequest to his daughter, it was with the proviso that the inheritance was conditional on her "not being convicted of any offence". A tantalising clue...

And yes, Annie's story is a sad one.. but at least in part, an adventurous one, and although Annie is not in our direct line of ancestors (that line goes through her brother Alfred), it's a story worth telling.

Married at 19, a mother at 22, in Holloway Prison at 25, all before being shipwrecked a year later off the west coast of Africa on her way to a new life in Australia. Well, the new life in the colonies didn't quite happen, or at least, it wasn't the life her father George had hoped for, when he set out in the 1890s on a rescue mission to take Annie from her troubled life in England back to the bosom of her family, newly settled in Newcastle, the second city of New South Wales.

From

when she was born in 1864 at Dover on

the English coast, Annie appears to have led a conventional life

in the bosom of her family with her parents, Inland Revenue

officer George Boddy, and his wife

Caroline. George and

Caroline already had six children

when Annie Charlotte was born to the then 42-year-old Caroline.

From

when she was born in 1864 at Dover on

the English coast, Annie appears to have led a conventional life

in the bosom of her family with her parents, Inland Revenue

officer George Boddy, and his wife

Caroline. George and

Caroline already had six children

when Annie Charlotte was born to the then 42-year-old Caroline.

By the time of the 1881 census, 16-year-old Annie was the only one of the couple's children still at home in Dundas Terrace in Woolwich, in London, but a close neighbor was young Charles Richards, a 22-year-old fitter and turner, living with his widowed mother. Charles' father had been a hotel keeper in Kent, but he had died many years previously.

In 1884, Annie and Charles married, and three years later, son Herbert Charles arrived.

A year on, in 1888, several of Annie's own family including her newly-widowed father George, made the big decision to migrate to Australia, to join others of the family already there. Annie, her husband Charles and their son stayed on in England, as did two of Annie's older brothers, George a saddler, and William a telegraph linesman.

(above and right): Holloway Prison, London

For the first 7 days of the scheduled six week voyage, all went well. Then disaster struck. Port Douglas was heading in to re-fuel at Dakar, in French territory on Africa's west coast when she struck a reef. The disaster was widely reported in Australia, including in the newspaper of George's new home town, Newcastle.

When

off the coast [of Dakar] the Port Douglas foundered in

about three fathoms of water, and after rolling about for some

time, drifted and struck a dangerous reef, which starts from

shore. The passengers, numbering 41 in all, took to the boats in

the hope that the vessel would bear up against the heavy weather

which was then raging. Those in the boats stood by the

vessel, which was fast breaking up.

When

the salvage schooner sent from Dakar hove in sight all haste was

made, and the small craft got alongside safely and a start was

made to salvage the luggage. This was quickly put on board the

schooner. The passengers and crew made for shore. Next morning

they walked to Dakar, and were hospitably received by the French

authorities. When the work of salvaging the cargo was proceeding,

one of the men engaged was washed away by the heavy sea

which struck the schooner. He was not seen again alive,

but portions of his body were picked up, when it was found that he

had been torn asunder by sharks.

That same year, she headed south to the capital, and before long, Annie Richards was coming unfavourably to the attention of the constabulary in Sydney, at first for such minor transgressions as drunkenness, offensive language and vagrancy. (There was at least one other Annie Richards on the wrong side of the law in Sydney at this time, but fortunately, court and jail records often noted the accused's ship of arrival in the colony. In Annie's case, this was sometimes recorded as Port Douglas,and in others, S.S Kaikouri).

Her offences were ones that in the 21st century would hardly raise any interest, let alone police charges, but times and sensibilities were different in the 1890s.

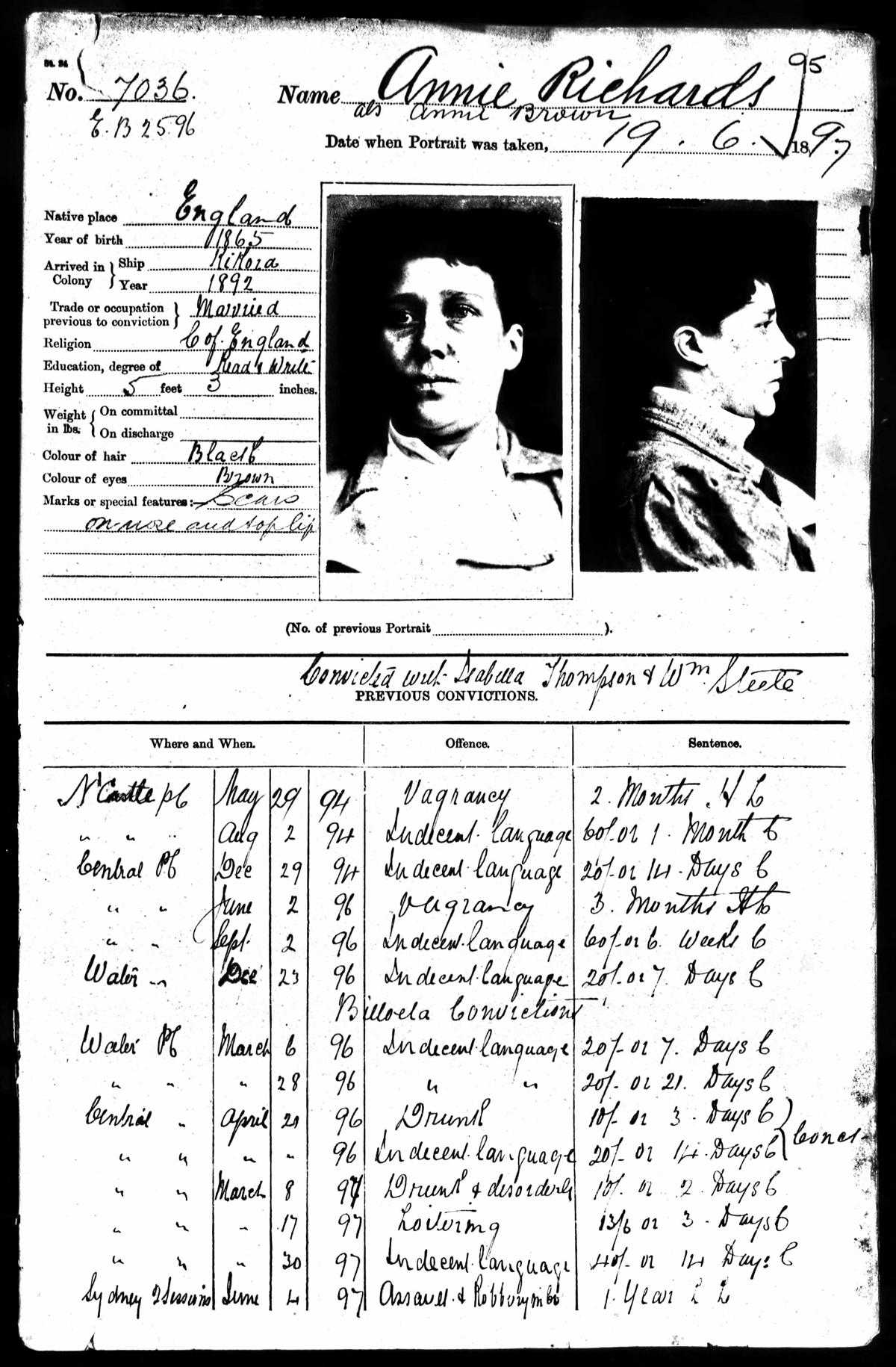

Nevertheless, that brought her a sentence of a year's hard labour in Darlinghurst jail. By this stage, the prison system had adopted the modern technology of photography, and so we have a photographic record of Annie and some of her transgressions.

Fortunately for those of us seeking to check family history, this record (below) listed the ship she arrived on in Australia (Kaikouri), and some distinctive scars (on upper lip and nose). It also notes an alias Annie used from time to time, Annie Brown. A later record (from East Maitland Gaol) shows both 'Richards' and 'Brown' as aliases for Annie Boddy, as well as the distinctive scars.

After her release, Annie, maybe thinking she'd be better off with her family in Newcastle, went back to her maiden name and returned to the Hunter – but if that were her intention, the good resolutions didn't last, and before too long, she was back in front of the local magistrates, once again for drinking and bad language. This brought her a certain notoriety, and she was described in the local paper as an old offender – and the newspaper was referring to the length of her rap sheet, not her age.

On one of her regular admissions to East Maitland gaol, the (difficult-to-read!) record in July 1900 lists her name as Annie Boddy, alias Annie Richards, alias Annie Brown, and as a confirmation of her identity as the woman involved in the assault and robbery offences three years earlier in Sydney, it also details the scars on her lip and nose and her ship of arrival as Port Douglas.

Perhaps father George still had hopes that his youngest daughter would reform. He left her a bequest in his Will, but carefully stipulated that she was to receive it only if she was not convicted of any offence. After George died in 1901, it was obvious that Annie wouldn't qualify for her inheritance.

By early 1904, she was living in a benevolent asylum in the Newcastle suburb of Waratah, where she gave birth to a son, John Oliver Boddy. Young John's father is not known, and the baby's life came to a premature end when he was only three months old. He died in Newcastle Hospital of 'heart failure' and was buried at Newcastle's main cemetery at Sandgate.

Given that she was out of favour with her

Newcastle relatives, it's

not surprising that Annie turned for help to

the one brother, Samuel, who had settled in Sydney in the 1880s

and who rarely came north.

After the death of her son, the next we know of Annie is

that she went to live with Samuel, at his home at Five Dock, in

Sydney. That's

where she was when her health deteriorated – and in 1909, Annie

died, of tuberculosis, at Sydney Hospital,

at the age of 44.

Her story was forbidden territory.

The Benevolent Asylum in the Newcastle suburb of Waratah, where Annie was living at the time of the birth and death of her baby boy. (This building still exists in 2020, and has gone through a couple of re-incarnations in its more than 100 year history).